Miho Sato

03.02.07 – 10.03.07

Miho Sato is something of a militant magpie for the information age. Borrowing at will from a variety of printed source matter, Sato liberates the images she chooses of the artificial facets that bind them to time, place and sentiment and gives them back to us devoid of detail. But there is a catch. In choosing to re–present familiar subjects, Sato forces us to confront just how complicit we are within the endless cycle of data reproduction. Rifling through other people's histories, she is free to shine a light under the murkier aspects of contemporary image making. Through the process of adding conceptual flesh to the bones of these paintings we become responsible for the sum of our marketable parts, yet essentially remain the victims of an astute pictorial setup.

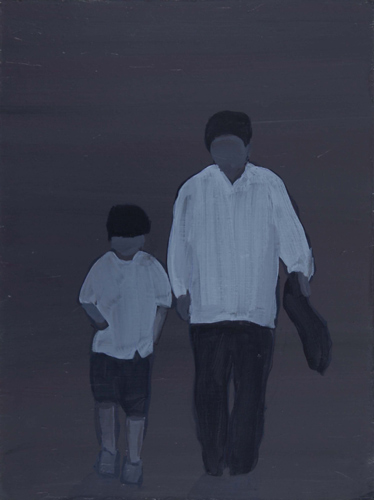

Absorbing the visual materials that please her, Sato appears to filter all extraneous data through a ruthless pictographic net until she is left with a partial, but strangely faithful version of the original. The contemporary icons, bit–part characters and creatures harvested for painterly post–mortem, have been stripped of the obvious qualities upon which we rely to inform us of who or what they are. The non–specific habitats within which we find these lost souls could just as easily represent limbo as a moment of conceptual clarity. These works are not fussy or precious in a realist sense, yet the painterly delicacy with which she describes her subjects is acute, though easily masked by the simplicity of the composition.

The title of Sato's last solo show at Domo Baal, 'Amnesia' in 2005, implied that the details left out of the portrait–like paintings had been forgotten. Almost as if the blank expressionless faces of celebrities and social stereotypes had been snatched from the subconscious of a coma patient. The new works have been suitably reduced: boiled down to a thin, grey acrylic soup and served up in small but deadly portions. Where earlier subjects appeared to pose grimly for Sato's studies, the new breed might have been caught unwittingly: whether National Geographic silhouettes hewn from barren landscapes, or characters caught in a celluloid moment purposefully ignoring any voyeuristic intrusion. They refuse to engage with us, passively aggressive in their silent request that we work out the dynamics for ourselves. In 'Cowboy film' a distant horse and rider surveying a mountain range, painted as if viewed through a lens, appear as though they might leap from peak to peak now released from the hobbles of pathos and schmaltz two defining characteristics of Western films and American pioneer painting.

Sato does not flatter her subjects. On their reductive journey from printed image to painted entity, her characters, like those in Haruki Murakami's Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, are forced to check in their shadows at the edge of the frame. But then, perhaps it is the shadows of these beings, who have been blocked out with a complex but limited range of colours on primed black boards, that we are really engaging with. The fill–in effect of the luminescent grounds from which the figures emerge simultaneously hoodwinks the viewer into thinking these paintings more crudely manufactured than they are, while affording a compositional breathing space within which to more closely examine Sato's tonal proficiency. The ground as void or contemplative space is a crucial feature in her paintings: the cinematic tension that binds the two figures, sat side–by–side and staring out into a nebulous spatial plane, in 'Shore' might just as easily signify the end of an affair as the advent of Armageddon. The stark honesty of earlier paintings seems to have softened slightly as if polluted by a vaporous belch of hope.

There is little room for vanity, for these facsimiles in acrylic elegantly straddle the intersection between the physicality of the character depicted and their associative other – their brand potential. While the images behind the paintings (Sato often sources visual material from the mainstream press), may promote a false, engineered beauty, she refuses to comply with the unattainable standards set by digital image–makers. Sato's production methods mirror the Photoshop phenomenon in reverse: camera–ready faces appear to have been wiped clean in a few brushstrokes. If during the painting process a head of hair should become a black helmet, a killer whale a fighter plane, then so be it, how we process and typify these associations is our lookout. Yet Sato is not ambivalent towards her subject matter; she is dogged in her pursuit of the image required, often producing several versions of the same painting.

These featureless characters are anything but forgettable; they hold our attention despite the fact that we have become sensorially anaesthetised to the high–tech trickery proffered by film and photographic media. Though potentially iconic in a contemporary sense, they are not the highbrow subjects often favoured by the English School of painters Sato makes reference to. 'Maria' (the earliest and largest work in this new series), arms held aloft, is not so much proclaiming that the hills are alive, as resignedly accepting her replicatory fate. A lone stag, pictured in the muted lilac landscape, more single–malt hinterland than natural world, trades on the benign cuddliness of the earlier 'Moomin' series, while operating as a symbol of Western consumption. Oddly though, these works appear quite at home when reproduced in digital format: through the process of downloading the images you experience that fantastical element so hard to define in these spare paintings as they materialise on screen. Many of the adjectives that accurately describe Sato's works (monochrome, melancholic, reductive) do little to explain this preternatural quality.

It's as easy to fictionalise Sato, as a foreigner living in Britain (she came to London from Japan to study at the Royal Academy Schools in 2000), as it is the characters she chooses to paint. As Ansel Krut points out in a recent issue of the quarterly painting magazine turpsbanana: "it is impossible to disentangle your own associations from her imagery". Sato's otherness is a palpable collaborative force fostered by the artist and projected by the viewer: it is the last component to be stripped from the residue of her painterly characters and the first ingredient absorbed through the viewing process. Upon meeting Sato it is possible to believe that the published protagonists, filmic antiheroes and art historical symbols that dominate these paintings arrive in her life through an alchemical, perhaps fatalistic process. But the fact that they press so many of our sensory buttons is no accident.

© Rebecca Geldard, London, December 2006

>Miho Sato: Planet Arbent, 2010 (link)

>Miho Sato: Amnesia, 2005 (link)

>Articulated Artists: Alli Sharma interviews Miho Sato, 2012 (pdf)

>Rebecca Geldard excerpt on Miho Sato from 'Oyster Grit', 2007 (pdf)

>Rebecca Geldard: essay on Miho Sato, 2007 (pdf)

>Ansel Krut: on Miho Sato, in Turpsbanana, 2005 (pdf)

>Jonathan Miles: essay 'Another Country' on Miho Sato, 2005 (pdf)

>Sue Hubbard: review, Independent, 2005 (pdf)

>Ros Carter: 'New British Painting' at John Hansard Gallery, 2003 (pdf)